The ultimate goal of a thesis or dissertation writing group is to help members of the group complete the writing required for a graduate degree, and have as positive an experience as possible.

What do grad students say about the experience of writing a dissertation or thesis?

- “A writing buddy was essential to staying motivated and productive.”

- “I felt really isolated before working in a writing group. It was great to see what other students were doing, and how we shared similar struggles.”

- “My writing group [of people outside my research area] really helped make my work more coherent and improve the logical progression of my thinking, so my supervisor could focus feedback on the content itself.”

- “Writing the dissertation was such an unbelievably long process. Connecting with others helped me keep perspective, especially when a new member joined who was just starting out. I saw I had made progress, and it felt great to encourage a more junior student.”

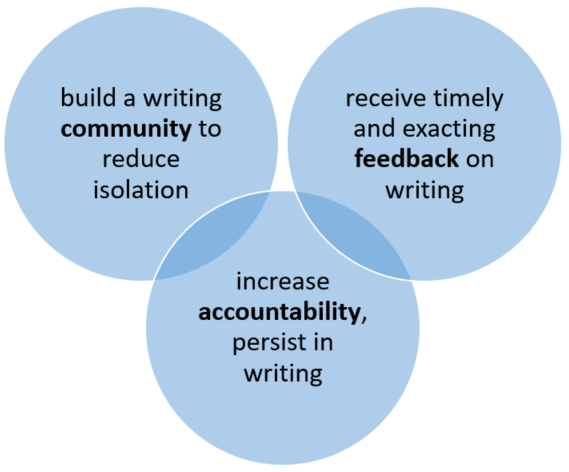

Graduate students might create or join a writing group to:

Another type of thesis writing group is a thesis writing support group, which is often psycho-educational in nature and led by a professional counsellor. This resource will only focus on peer-driven groups.

There is no formula for creating a group, but here are some things to consider:

- MA or PhD students?

Given the different expectations in an MA thesis vs. a PhD dissertation or manuscript, it may be preferable to seek members working at the same level.

- Same research field, or different departments?

If members are in similar fields, they share a general knowledge base, which may be helpful if they offer feedback on each other’s writing. On the other hand, if members come from different fields, they may be more open to divergent interpretations or ideas, more likely to take creative risks in their thinking, and less competitive (e.g., for supervisor’s time, grants, jobs) or less concerned over intellectual property rights.

- Similar or different stages in the writing process?

Some groups prefer members to be at various stages from proposal writing to final editing, so more experienced students can mentor and encourage less experienced students. Some groups want members to be at similar stages, to share a common experience.

- Open or closed membership?

An open writing group, with members who just show up to write on a regular basis and then leave, can more readily have an open membership. These groups often pop up (and disappear) independently in departments, or through the School of Graduate Studies or the Society for Professional and Graduate Students at Queen’s.

Closed groups have a fixed and committed membership that enables trust to develop. These groups may have expectations for adding new members, duration of membership, and departing members.

- Members who are currently friends or currently unfamiliar to each other?

The person who initiates the group typically will have an influence on soliciting members. It is important that members believe they can be comfortable, trusting and respectful with each other, especially if the group will be interactive.

- Large or small?

Depending on the purpose served, the group can be very large (60?) or rather small (6?). Other factors, like being able to find available space and a common meeting time, may influence the size of the group.

Clarifying the writing group’s purpose and structure is critical. For more detailed information on this topic, please see the Stanford University Hume Writing Centre’s Starting an Effective Dissertation Writing Group and the University of Minnesota’s Getting the most from a writing group.

It is also important to establish the group’s boundaries. Completing a thesis or dissertation is very demanding and often challenges a student’s sense of self-worth and professional direction or ambition. A peer writing group is not a therapy group, although there may be emotional and psychological benefits to participating in a writing group.

Students with concerns for their sense of self or well-being should speak to a trusted professor, mentor or counsellor. Counsellors are available to full- and part-time students through the Queen’s School of Graduate Studies or through Student Wellness Services.

Writing groups often fall into one or more of the following categories: community-based, accountability-based, and feedback-based.

Accountability-based group members usually

- set “public” deadlines for completing specific tasks, in person, an online social media group, or a shared Google doc

- check in with each other’s progress

- acknowledge each other’s successes, and encourage each other through setbacks.

One online accountability site is Phinished.org, where writers can make pacts about how much they will finish. Students who want to “show off” their accomplishments might use 750words.com, where students earn points for daily writing and can display their badges on Facebook.

Community-based group members usually develop

- community norms for noise, conversation, internet use, food, timing, attendance, etc.

- a structure for breaks, start and end times, social chat time, and perhaps writing exercises

There are no “rules” to follow, but a format for a community-based group might include:

- A check-in from each member about events of the week, progression on goals, new barriers or issues to be resolved (maybe 2-3 minutes per member).

- An educational or problem-solving discussion of new or persistent issues (maybe up to 20 minutes). This discussion could include brainstorming solutions, an invited speaker, a group member presenting on a hot topic, or a discussion of a relevant writing technique.

- Time to set SMART writing goals for that writing session and for the upcoming week (5 min)

- Writing time (1-2 hours?). The group should agree how much time they would like to spend writing, and when they will take breaks. Breaks support focused, creative thinking. One way to use a longer writing period is to break up the time like this:

Write for 80 minutes, then break for 10 minutes

Write for 60 minutes, then break for 10 minutes

Write for 10-15 minutes to review the writing to identify issues or unclear thinking. Then, write down a question to ponder until the next writing session. Start the next session by writing a response to that question, or discuss unanswered questions with the group or thesis supervisor.

- Time to socialize after writing (maybe 15 minutes).

Every group needs to work out a format that meets the needs of the members, and is manageable and sustainable.

If your group is designed for feedback, the group

- shares their work. Some standard systems for writing, editing and collaborating online include Google Docs, OneNote (Outlook) and Dropbox

- sets expectations and norms for the amount of time any one person will spend on feedback

- determines the focus of the feedback (content vs writing style) and for when writers need to share with the group

- members specify what kind of feedback they want, and direct readers to specific concerns.

The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill offers a thorough list of questions to help feedback-based groups set expectations and norms.

In addition to the possible elements of a community-based writing group, feedback-based groups include time for writers to share their work and receive feedback. Some groups will choose to devote their time to feedback only, and save writing time for non-group time.

Writing groups usually include time for writers to share their work and receive feedback.

The following content is based on work by S. Lee and C. Golde.

Asking for feedback

Feedback groups need to consider:

- how to schedule feedback: sign-up list, regular rotation, informal approach

- whether to distribute materials in advance or present material during the group

- clarifying what writing projects might be acceptable for requesting feedback: outlines? first drafts? polished drafts? conference papers? whole works vs chapters or sub-sections?

Writers seeking feedback should offer a brief overview of the piece’s purpose, audience and key ideas, their own current assessment of it, and a specific request for structural, stylistic or other feedback. The piece should be short enough to allow the group members to review it in a reasonable time frame. Writers seeking feedback should not treat their group members as proofreaders.

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is a skill, but it starts with intention. Are you there to support the writer or show off your own skills? Be sensitive and helpful, and remember that soon it will be your turn to hear what others think of your writing.

It is a rare opportunity for a writer to hear from others in a “safe space.” Respond with specific references to their work, using language that is clear, non-judgmental and leaves room for the writer to further explain themselves. Avoid overwhelming the writer with too much feedback. Offer praise as part of your feedback; every piece of writing has something praiseworthy about it. Speak as a thoughtful reader, not as an all-knowing judge, and stick to the type of feedback that the writer asked for.

Receiving Feedback

It is an act of courage to request feedback and then listen with an open mind to what is offered regarding your writing. You may not agree immediately (or ever!) with all that you hear, but it is a privilege to have people spend time thinking about your work, so it behooves you to pay attention and sort through comments later.

To accept feedback gracefully,

- listen to the entire feedback first, and try to understand the meaning of the feedback. Write down notes and questions.

- be engaged. If anything is unclear, restate your understanding of what you thought the speaker said.

- be respectful. Try not to be too defensive. Even if a reader’s response is due to a misinterpretation of the writing, their perspective deserves attention. If several readers agree that a section is confusing, the problem probably lies in the writing.

- keep a feedback log. Keep track of the kinds of feedback you get. Identify common themes. Address problems with your writing group, or visit the Writing Center or your supervisor.

The group’s planning and organization could be determined in advance by one person who initiated the group, or they could be negotiated among members during an early meeting. Some logistics to consider:

- Where will the group meet? On campus or off? What facilities will be needed, depending on the purpose of the group ( e.g., tables, white board, data projector, multiple power outlets)? Rooms on Queen’s campus are available:

- group rooms in libraries, booked by students

- the Kingston Frontenac Public Library (613.549.8888) has small bookable meeting rooms

- When and how frequently will you meet?

- What are the expectations around attendance and preparation (e.g., for a feedback-based group)? What is the consequence of failing to keep the commitment?

- How can new members join, and what is the process when a member decides to leave?

- What work can be brought for feedback? Initial ideas or outlines or rough drafts or polished drafts? Research proposals? Thesis or dissertation writing only? Conference presentations? Publication submissions? Grant proposals? Job applications or CVs?

Depending on the focus of the dissertation writing group, there may or may not need to be a leader. For example, an online accountability group like Phinished.org has a web manager rather than a leader.

A group aimed at increasing community may not require a leader, but may need someone to book rooms and communicate with members.

A feedback-based group will benefit by agreeing on a leadership or organizational model. Members may decide to have a single leader or rotate the leadership, to manage or delegate tasks such as:

- scheduling meeting times

- booking rooms

- communicating among members

- setting the agenda and facilitating the meeting (e.g., who presents work for feedback, selecting writing activities, inviting quest speakers, etc.)

- keeping the meeting on track and on time

- note-making for feedback

- bringing the cookies 😊

- setting up and/or cleaning up the room

Another logistical decision is: will the group be open or closed in membership?

New members may be added to a closed feedback-based writing group once an established member completes writing their dissertation, or no longer wishes to be part of the group. Generally, the culture of a closed group will be better maintained if a group member talks to a prospective member before inviting them to join, in terms of

- their writing goals (does this group meet their needs?)

- their ability to make the same time/space/duration/ possibly “feedback homework” commitments of the existing members

- whether they appear to be compatible with the existing members

Some groups might choose to vet prospective members for “fit” or have a trial period before the prospective new member has to officially join the group. As new members join, there usually is a period of re-adjustment and a shift in the developmental stage of the group.

Endings are inevitable, and often generate mixed feelings: “YEAH, I did it! But I’m going to miss you so much!”

Individual members of a feedback-driven group will leave as they complete their own projects or the group may disband as planned after some period of time, or just dwindle out. Ending a feedback-based or community-based thesis writing group hopefully signals great accomplishments for members.

Regardless of the reason, the end presents an opportunity for self-reflection, either individually or as a summative exercise by the whole group. Some reflective questions to consider:

- How did this group help me meet my personal goals?

- Are there ideas or work habits or activities that would be useful to include in my future large writing projects?

- What can I take away and quickly put into practice in my academic life?

- Is there unfinished work (personal or professional writing or activity) that I need to complete? For example- do I need to reduce my fear of speaking in public?

- Can I get ideas or resources from the group to help solve a particular problem before we end?

Interested in joining an accountability- and community-focused writing group? Sign up for Grad Writing Lab.