Literature Review

A literature review is most often part of a larger document like a research report, where it serves to describe, from broad to narrow, the context and purpose for a particular research study. A well-written literature review both summarizes and synthesizes the available literature. It is not enough to list and describe sources. Analysis is required (e.g., asking “so what” or “what does it mean;” discussing how sources interact or relate; demonstrating patterns and relationships).

PURPOSE. The purpose of a literature review is to map out a topic in order to provide the necessary context for your research questions or thesis statement: it tells the reader what is known, what gaps remain, and how the current study will add to the body of knowledge. As such, its purpose is to set the stage for what is to come.

NOTE. There are general principles of literature reviews, but they also vary by discipline and function. When in doubt, or if something conflicts, check with your professor or advisor.

Plan your assignment now:

STAGE 1

Planning

Good planning supports both the research and writing you will do for your literature review. The planning phase encompasses understanding the task, selecting a topic, and determining your purpose. Here are some strategies for managing large writing assignments.

Understand the task

This should take about 1% of your time

Begin by understanding the requirements (e.g., how many and what type of sources, page number, format/reference style) of a literature review in your field.

Try asking your advisor/professor to recommend a good model of a literature review. Ask him/her what makes it a good model. Read it and take note of elements to emulate (e.g., organization, manner of discussing and linking findings, etc.).

If you have questions, be sure to ask your professor or advisor early in the process. Give yourself some structure by setting deadlines (e.g., “On [DATE], I’ll meet my advisor/professor to discuss the first draft of my literature review”).

Topic

This should take about 2% of your time

Whether you are selecting a topic from a list of options for a class assignment or are narrowing a broader topic for your thesis work, this step is about defining the subject and scope of your review.

This process organization chart can help to guide your topic selection: start with a working topic, review the literature, and then narrow your topic accordingly. Some general tips on how to choose a topic may be helpful.

Purpose

This should take about 1% of your time

Once you’ve narrowed your topic, determine the problem or purpose for your literature review to address. The goal of your literature review is to set the stage for the argument you wish to make or the research questions you will ask.

You may have research questions in mind; they are not strictly part of your literature review but what you are leading up to. Having strong, clear research questions, if applicable, will inform your literature review’s purpose. Be sure to understand the purpose of your literature review before moving on to Phase 2 (Research).

Many students find it helpful to check in with their professor or advisor about their topic and purpose to make sure they’re on the right track.

STAGE 2

Research

Now that you have clarified your topic and purpose, it’s time to research. First, develop a research strategy. Then, read and take notes, and analyze your sources. Note that the research process is almost entirely iterative. The decisions, actions, and evaluations you’ll make will occur cyclically, not linearly.

To keep yourself on track, stay within the parameters you established in Phase 1. That is, your goal is to provide the reader with the essential context for your purpose. Do not feel you need to read and cite everything ever written on your topic! Literature reviews are not exhaustive, encyclopedic documents. Keep your purpose as your focal point.

Develop your research strategy

This should take about 12% of your time

Develop a search strategy:

- Creating an effective search strategy (Purdue University Libraries, YouTube video)

- How to formulate a search strategy (University of Saskatchewan, with embedded videos)

Get expert help from a subject librarian with relevant content-area expertise. The librarian can help you figure out how and where to search, what keywords and which databases to use, and how to know when you’re done searching.

HINT: Use the reference list from seminal or particularly relevant papers as a springboard!

Keep track of the papers you find with citation management programs from Queen’s Libraries. (They’ll also help speed up the creation of your reference list later!) You can also use a spreadsheet to manage your literature review—this is especially helpful if you’re researching a fundamental or particularly expansive topic.

Reading and note-taking

This should take about 20% of your time

To read effectively you need to read actively. Keep your purpose in mind when you read. With each paper, ask, “What is this going to do for me?”

Try the three-pass method:

- First, PREVIEW the paper. Read the title, the abstract, and the discussion. Is it relevant for your purpose/topic?

- If it is relevant, read the paper. Keep notes to a minimum; focus on understanding it.

- Then, READ it again, this time taking notes with a specific purpose in mind (e.g., summarize, short quotes, evaluations).

A structure like the Matrix Method or Cornell Notes may help you select and organize the information you record for your literature review. Here is an example of the matrix method from a Health Sciences lit review.

As you collect relevant sources, stay focused and ask yourself questions like these.

Analysis

This should take about 15% of your time

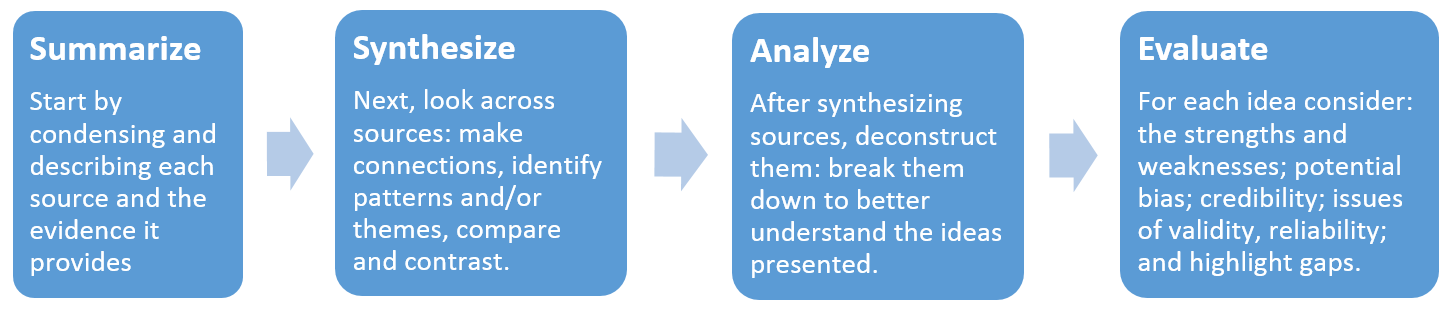

Now that you’ve reviewed the literature, selected relevant sources, and made notes about pertinent papers, it’s time to analyze and interpret the information. Four skills are especially important for this step: summary, synthesis, analysis, and evaluation.

Here are some guiding questions to support each of these skills. Analysis and interpretation will ensure that your literature review will support your purpose and will prevent you from writing a disjointed list of sources.

STAGE 3

Writing

Phase 3 begins with an outline or a writing plan; then, write a first draft of your literature review. Check what you’ve done by constructing a reverse outline or by comparing what you wrote to the outline you created prior to your draft. Then, revise and edit; expect to need at least three drafts before your paper really comes together.

Write an outline

This should take about 5% of your time

At this point, you’ve got a lot of information! Now it’s time to make a plan that will support your writing process.

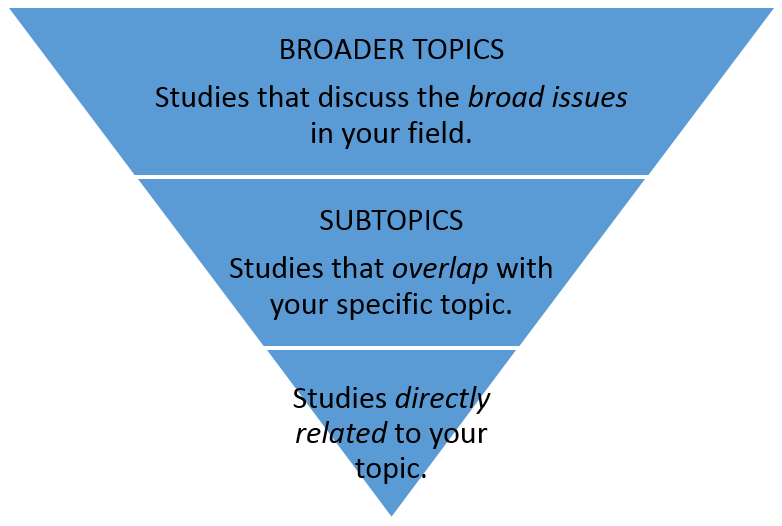

What do you need to say and what order makes the most sense? The answer depends on your purpose. Literature reviews are frequently organized from broad to narrow: introduce the problem/purpose, then highlight major developments in the area before identifying the gap and how your research relates. (See diagram.)

Tip: Write your purpose and/or research questions on a sticky note and keep it nearby. It’ll help to keep you on track as you write!

Write the first draft

This should take about 15% of your time

Right now your only job is to get words on the page. Don’t worry about making it perfect. Try not to edit as you go—just write. Just because you wrote an outline doesn’t mean you have to start at the beginning and write straight through to the end of your literature review; start with something easy and build writing momentum!

Having trouble? Check in with some of the reasons why that might be, or try some of the strategies listed here, like free writing, goal setting, and positive reinforcement. Here are some resources specifically for writing as a graduate student.

Construct a reverse outline

This should take about 2% of your time

A reverse outline can help you confront two common problems with literature reviews: poor organization and poorly articulated purpose. Here’s how to develop a reverse outline, plus a slightly more in depth discussion of reverse outlines for literature reviews.

Remember to use your purpose as a guide; reflect on what you know, what’s been done, where the gaps are, and how it all fits together.

Revise/write a second draft

This should take about 20% of your time

Revision is about the big picture: whether your purpose is clear, whether you’ve effectively synthesized and analyzed the sources you’ve cited, the logic flow of the paper, etc.

- Recall that the key to a good literature review is synthesis—you must do more than list sources and findings (e.g., going beyond “X showed…, and Y demonstrated…, then Z suggested…”).

- Literature reviews benefit from multiple revisions: think of revision as happening in stages. To focus the task and make it more useful/helpful, pick a specific goal each time you revise (e.g., “This time, I’m only paying attention to content—next time I’ll check the structure”).

- Revisions might be done both by you and with feedback from others. (TIP: Revise your own paper first, at least once, before showing it to someone else for feedback.)

Resources to support revision: check your paragraph structure and coherence; improve flow and coherence with strong transitions; organize the essay body; and integrate sources in your writing.

Edit

This should take about 5% of your time

Once you have a draft you’re happy with you can turn your attention to your paper’s sentence structure, word choice/vocabulary, and grammar. You’re aiming for style and coherence, correcting awkwardness, making sure transitions are clear, etc.

Here are some of the most common errors in style, grammar, and punctuation.

Proofread

This should take about 1% of your time

One last look! This is your last chance to find that annoying typo.

It can help to read your paper backwards (sentence by sentence or paragraph by paragraph); you’re more likely to catch typos this way because you can focus on form, not content.

Submit

This should take about 1% of your time

Congratulations—you did it!

Take some time to reflect on what you learned by writing your literature review. For example,

- What do you now know about the content related to your research questions? About your field?

- How will the context you examined be important for your process going forward?

- How will the contents of your literature review inform the Discussion section of your thesis/dissertation?